Chloe Wise

“Thank You For The Nice Fire”

New York, 39 East 78th Street, 2nd Floor

Chloe Wise is preoccupied by the political chaos in the United States, amidst a global pandemic, wherein shared concerns surrounding health and hygiene are in conflict with the individualistic desire for liberty and comfort. We want to butter our toast, eat it too, and cleanse our hands of it immediately. Over the course of the past year, Wise’s gaze, like that of many, has turned inwards; her field of view impacted by the lessened exposure to the hyperreal billboards that frame the urban landscapes of New York, where the Montreal-born Wise is based.

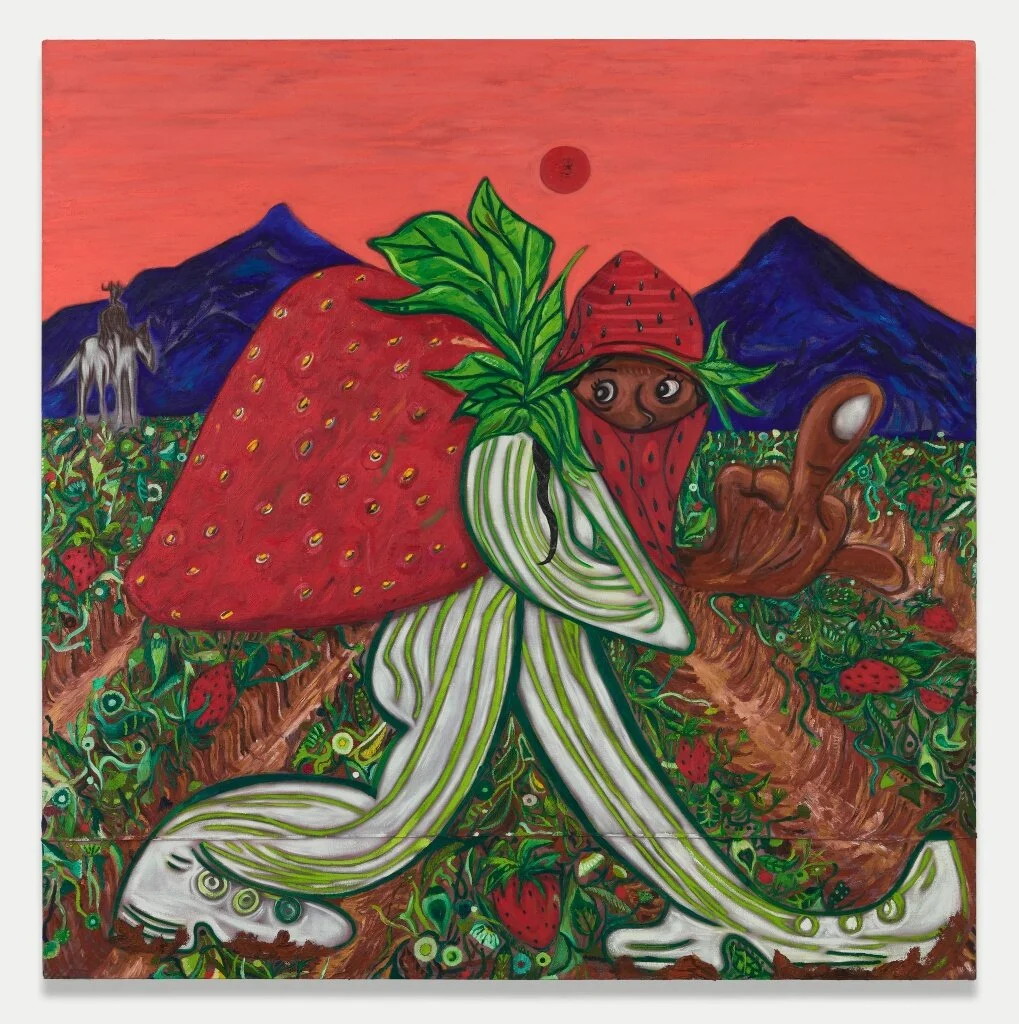

Chloe Wise, Lactose Tolerance , 2017 Oil on canvas 210 x 300 cm 82 5/8 x 118 1/8 inches

How do we conceptualize experience when many of us are spending inordinate amounts of time indoors, with limitations imposed on our habitual ways of accessing the world? Time ticks on, as evidenced by the changing of the seasons and the rotting of produce, the dispassionate proof in the parabolic pudding. Picture a TV set left on in an empty room, the flickering of the television ‘ultimately addressed to no one at all, delivering its messages indifferently, indifferent to its own messages’ (Baudrillard 1986). The world turns, we stagnate.

““This is the only country which gives you the opportunity to be so brutally naive: things, faces, skies, and deserts are expected to be simply what they are. This is the land of the ‘just as it is’.”-Jean Baudrillard, ‘America’ (1986)”

In this series, Wise proposes scenarios of simulated familiarity, where smiles, hand gestures, and utterances are at odds with underlying realities, such as widespread uncertainty, willful ignorance, growing inequality, and aspirational notions of “unity” that reinforce a status quo. Underneath (or alongside) the comfort of platitudes resides the chaotic potential of the abject.

In Baudrillard’s experimental travelogue ‘America’ (1986), he cross-examines the American smile in postwar America and its own travel within Reagan’s America:

“The smile of immunity, the smile of advertising: ‘This country is good. I am good. We are the best’. It is also Reagan’s smile – the culmination of the self-satisfaction of the entire American nation […] Smile to show how transparent, how candid you are. Smile if you have nothing to say. Most of all, do not hide the fact that you have nothing to say nor your total indifference to others.”

As we exit Trump’s vision of the United States, a neo-Reaganist formation that sought to recuperate the exclusionary tactics of American suburbia in a settler-colonial state, we find ourselves faced with the task of re-establishing a belief in truth. In a post-truth era, where everything (and simultaneously nothing) is true, where staying home is safe because others are “dangerous,” we risk losing our common connection to a verified reality. “If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle,” historian Timothy Snyder writes in ‘On Tyranny’ (2017). Indifference and distrust permeate our so-called “new normal,” yet we continue to produce and consume signifiers of the time before. We smile and wave, through mandatory reflex, to maintain a semblance of normalcy.

-Kristen Cochrane

Doctoral Researcher, Film and Moving Image Studies

Concordia University